Dr. benazzato luca

MODELLO PER IL CURRICULUM VITAE I I NF MEDICI Dirigente medico a rapp.esclusivo TITOLI DI STUDIO E PROFESSIONALI ED ESPERIENZE LAVORATIVE Dal 26.06.01 al 30.09.01 medico assistente medicina c/o la Casa di Cura Abano Terme (Presidio Ospedaliero USSL 16, Padova) Dal 1 gennaio 2006 al 30 settembre 2007 medico a contratto libero professionale per l’attivazione e il consolidamento dello sc

SEMINARS IN RESPIRATORY AND CRITICAL CARE MEDICINE/VOLUME 29, NUMBER 5

Table 1 Nomenclature for Mycobacterium aviumComplex (MAC) Organisms

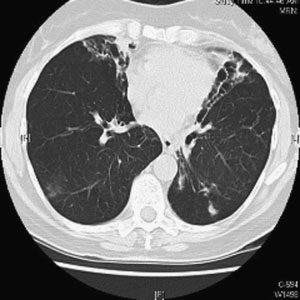

Figure 1 Chest computed tomographic scan. Right upper

lobe cavitary opacities in 63-year-old man with Mycobacter-

ium avium complex infection and underlying emphysema.

SEMINARS IN RESPIRATORY AND CRITICAL CARE MEDICINE/VOLUME 29, NUMBER 5

Table 1 Nomenclature for Mycobacterium aviumComplex (MAC) Organisms

Figure 1 Chest computed tomographic scan. Right upper

lobe cavitary opacities in 63-year-old man with Mycobacter-

ium avium complex infection and underlying emphysema. DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT OF INFECTIONS DUE TO MYCOBACTERIUM AVIUM COMPLEX/KASPERBAUER, DALEY

with tuberculosis, isolation of a single positive sputumculture does not necessarily represent disease so diag-nostic criteria have been developed to aid the clinician indeciding whether treatment is indicated. Unfortunately,well-designed and appropriately powered studies for thetreatment of immunocompetent hosts are still lacking.

DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT OF INFECTIONS DUE TO MYCOBACTERIUM AVIUM COMPLEX/KASPERBAUER, DALEY

with tuberculosis, isolation of a single positive sputumculture does not necessarily represent disease so diag-nostic criteria have been developed to aid the clinician indeciding whether treatment is indicated. Unfortunately,well-designed and appropriately powered studies for thetreatment of immunocompetent hosts are still lacking.